Stories of hope, heartache and happiness hiding in the humble handkerchief –

Who could imagine that a simple square of cotton or silk could hold memories of sadness, loss, joy, hope, happiness and love in their evanescent folds? But they do. I know because over the years, I’ve heard countless stories from people about a handkerchief they treasure. Some hankies have been saved for decades. Personally, I have handkerchiefs in my collection dating back to 1893. True collectors have hankies that stretch much farther back in time, for these keepsakes were special to someone, and were thus saved, and survived for us to savor.

Handkerchiefs have been with us in the small moments – dabbing a baby’s chin, wrapping a child’s cut finger, catching a tear while watching An Affair to Remember for the umpteenth time, and the major moments – a bride’s tears of joy, a widow’s deep despair, a marine tucking his wife’s perfumed hankie over his heart.

Numerous histories of the handkerchief abound, with some facts contradicting others. In no way should you consider me a historian, nor this a comprehensive history. I offer the following as a compendium of fascinating facts gathered from a variety of sources that appear to be reliable.

History

Some historians opine the handkerchief originated in China, and was first used to shield a person’s head from the hot sun. Statues dating as far back as the Chou dynasty (1000 BC) show figures holding decorative pieces of cloth. Christian tradition links the handkerchief or sudarium to the Shroud of Turn offered by Veronica to Christ. The Romans waved handkerchiefs in the air at public games, and the drop of a hankie would signal the beginning of the chariot races. During the middle ages, a knight would tie a lady’s handkerchief to the back of his helmet as a good luck talisman.

The Handkerchief by Paolo Peri,

Zanfi Editori, 1992, pg. 10

In the fifteenth century, European traders returned from China with great numbers of peasants’ headscarves, which Europeans appropriated as fashion accessories. Renaissance portraits show both men and women holding handkerchiefs embroidered and edged in lace.

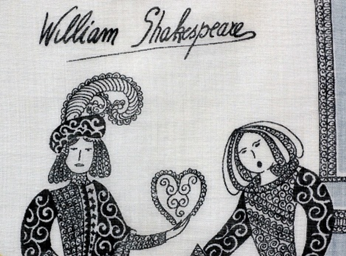

Handkerchiefs appeared in Shakespearian plays – Cymbeline, As You Like It, and most memorably Othello, in which a misunderstanding over a handkerchief caused Othello to kill his wife and then himself.

Handkerchiefs appeared in Shakespearian plays – Cymbeline, As You Like It, and most memorably Othello, in which a misunderstanding over a handkerchief caused Othello to kill his wife and then himself.

Once considered so valuable they were listed in dowries, as well as bequeathed in wills. The loss of a handkerchief was found recorded in publications as far back as 1665.

In Persia, they were considered a sign of nobility and were reserved for kings. Aristocrats sitting for their portraits would request that a handkerchief be included in the picture, the more embellished the better, to indicate their status and position.

Considered a symbol of wealth, handkerchiefs became larger and larger, until, in 1785 Louis XVI issued a decree prohibiting anyone from carrying a handkerchief larger than his. Good grief!

Considered a symbol of wealth, handkerchiefs became larger and larger, until, in 1785 Louis XVI issued a decree prohibiting anyone from carrying a handkerchief larger than his. Good grief!

The tradition of borrowing a bridal hankie may have stemmed from the times when they were too expensive for a young bride to afford.

Speaking of brides and courtship the handkerchief served as a surreptitious go-between to send explicit messages to the gimlet eyed observer.

Soon a whole language of flirting developed which survived well into Victorian times. It was said that Queen Elizabeth I, who carried handkerchiefs embroidered with gold and silver thread, created a whole vocabulary of hankie gestures for dealing with her staff.

Soon a whole language of flirting developed which survived well into Victorian times. It was said that Queen Elizabeth I, who carried handkerchiefs embroidered with gold and silver thread, created a whole vocabulary of hankie gestures for dealing with her staff.

Royalty notwithstanding, handkerchiefs for the average man were mostly white in color well into the 1920s. If a lady wished embellishment, she would personally embroider colorful flowers or other images on her hankies.

1930’s

During the depression, a handkerchief was often the only new item a woman could afford enhance her wardrobe. A woman would “change” her outfit by changing her hankie.

Continuing on through WWII, the hankie played a role in fashion. In addition to eschewing silk stockings so our troops could have parachutes, women would forego the pleasure of a new hat or blouse, and instead opt for a “wardrobe” of handkerchiefs, most costing .05 – .50. Everywhere you looked, hankies could be seen peeking from breast pockets or draped over a belt as a fashion accessory. Manufacturers like Burmel and Kimball advertised a handkerchief of the month in Vogue magazine. With the perfection of color-fast dyes, a vast array of cheerful colors allowed artists the freedom to depict everything from flowers to animals to cocktail recipes. There were handkerchiefs to celebrate holidays, birthdays, get well greetings, Mother’s Day, and more, often sold in special gift cards. Several years after the war, once fashion began to revive, Balmain, Dior, Rochas and other designers utilized handkerchiefs as a final touch to their haute couture. Hankies were tied to the wrist, threaded through the top buttonhole of a suit or popped from the side pocket of a handbag.

I must add here a most interesting exception to the rule of no silk hankies during the war – the next time you see a photo of a dashing aviator with a scarf trailing around his neck – look closely. Many kerchiefs were imprinted with maps of the countryside where bombing missions were carried out. Should these young men have the misfortune to be shot down, they literally held an escape map in their hands. Hundreds of hankies were printed during both WWI & WWII for soldiers to carry and/or give as mementos.

I must add here a most interesting exception to the rule of no silk hankies during the war – the next time you see a photo of a dashing aviator with a scarf trailing around his neck – look closely. Many kerchiefs were imprinted with maps of the countryside where bombing missions were carried out. Should these young men have the misfortune to be shot down, they literally held an escape map in their hands. Hundreds of hankies were printed during both WWI & WWII for soldiers to carry and/or give as mementos.

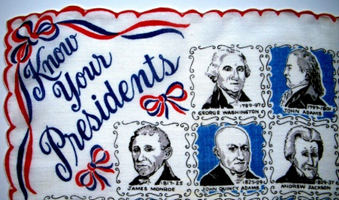

Handkerchiefs were even employed for advertising in political campaigns. One historian claims Martha Washington created a handkerchief to help promote the election of her husband.

Apparently she had “George Washington for President” hankies printed for distribution at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. To this day, handkerchiefs are printed depicting both Republican and Democratic parties, as well as coronation handkerchiefs for royalty. There is even a handkerchief that contains King Edward’s abdication speech.

Apparently she had “George Washington for President” hankies printed for distribution at the Constitutional Convention of 1787. To this day, handkerchiefs are printed depicting both Republican and Democratic parties, as well as coronation handkerchiefs for royalty. There is even a handkerchief that contains King Edward’s abdication speech.

The birth of Kleenex sounded the death knell for handkerchiefs. Originally invented in the 1920’s as a face towel to remove cold cream, by the 1930’s Kleenex was touted as the antidote to germs with their slogan “Don’t carry a cold in your pocket.” Many opted for a disposable alternative. In the mid-1950s, a Little Golden Book featuring Little Lulu, had an astronomical first printing of 2.25 million copies!!! showcasing “Things to make and do with Kleenex tissues featuring Lulu and her magic tricks,” showing children how to make bunny rabbits and more from tissues.

Busy housewives eagerly embraced the disposable hankie. It eliminated the school ritual of Show and Blow. This practice began in the 1800s, when, in the interest of hygiene, children were required to bring a clean handkerchief to school daily. To assure their offspring appeared spic and span every morning, clever moms devised the two hankie solution – one for show, and one for blow. Children always had a clean white hankie ready for inspection, while a utilitarian one often made from dress calico was in the other pocket! In Japan, ladies purportedly have a pocket in the left sleeve of their kimono for a utilitarian hankie and a lovely fashion hankie in the right sleeve.

See the U.S. A. in your Chevrolet……

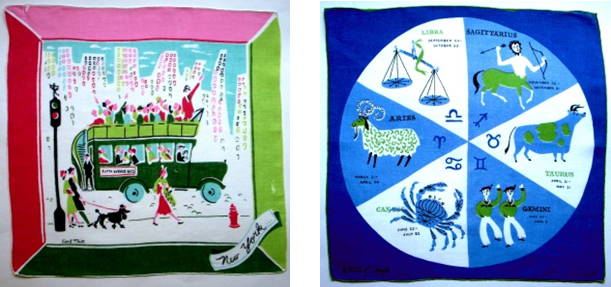

The growth of urban highways, automobiles, and “see America” vacations in the 1950s resulted in a burst of souvenir handkerchiefs, with Florida and California being the most common, as they were vacation destinations. Hankies featured famous cities and historic landmarks. Overseas travel prompted themes of Bon Voyage, cruises and foreign capitals.

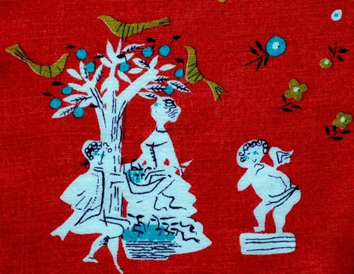

Little Works of Art

The heyday of hankies flourished in the ‘50s. Clever, creative commercial artists were given free rein on the “small canvas,” allowed to sign their work and see it featured at Lord & Taylor, Neiman Marcus and other specialty stores. Hundreds of new designs were produced annually, providing a plethora of choices for collectors today.

Handkerchiefs depicted everything from Christmas carols to nursery rhymes, recipes to foreign phrases. From birthdays to boy scouts, weddings to funerals, whether showcased as the centerpiece of a quilt, or fashioned into a christening bonnet, think of an occasion, and the hankie was surely there. I hope you’ll enjoy what we have to offer here.